- Home

- Julia Slavin

The Woman Who Cut Off Her Leg at the Maidstone Club Page 2

The Woman Who Cut Off Her Leg at the Maidstone Club Read online

Page 2

“I am the father.”

“Really?” Bruce cried. “I’ll be right home.”

“What are you going to tell Bruce when the kid only grows to be five-two with a big head?” Chris said, as I stacked fresh towels in the linen closet.

“You’ll grow into your head.”

“I’m full grown,” Chris said. “My dad has a big head and his dad had a big head and my mom has a big head too.”

Bruce and I had a beautiful evening, which we hadn’t had in a long time. We went for a walk in the park and sat out back on the deck and ate cherries. I begged Chris to go to sleep so we could be alone, and he did.

“You’re going to have to stop singing that song,” I told Chris one morning at my loom. Chris only slept when I slept now so I never had any time alone anymore. He was always singing bad music and moving around and he had to eat all the time. I felt fat and exhausted.

“It’s Lizard Savior. It’s great music.”

I threw the shuttle back and forth through the shed.

“That’s not music,” I said. “Beethoven is music. Mozart is music.”

“That’s boring music. And you think it’s boring too, if only you’d admit it.”

“Your Lizard Saviors are insipid.”

“What’s insipid mean?”

The shuttle got tangled in the weft and I got a yarn burn on my thumb. “Ouch, dammit. I need some time alone. Go to sleep.”

“I’m not tired.” He tickled an ovary with his boner.

“I’m not in the mood.”

“You never are these days.” He entered my ileum.

I tried drinking a pitcher of ice water, but by the time it made its way through my pharynx and esophagus, it sprinkled on Chris’s head like a warm shower. I thought of downing a pint of Wild Turkey to put him out but I was worried about harming the fetus. My hands were tied. He could do whatever he wanted.

“I want him to play football,” Chris said, pulling out of my appendix.

“No child of mine is playing football. Too dangerous. He can play baseball. Anyway, what if it’s a girl?”

“It’s a boy.” I put my hand on my middle and started to cry. I was carrying a boy, a son.

Early the next morning a soft trembling in my belly woke me. Chris was crying.

“Chris?” I felt around for his head, found it resting on top of my uterus, and patted it through my skin. “What’s the matter?”

“You’re having a miscarriage,” he said, and wept. I wrapped my arms around myself. “Five o’clock today. The baby’s dead.”

“What happened?”

“Defective implantation,” he said.

“All your moving around. You did this.”

“No!” he cried.

“You’ve been fucking me all over the place. I knew it was dangerous.”

“It was my child too. I know you feel bad, but I feel just as bad.”

“You don’t have any idea how I feel.” I ran down to the kitchen.

“Yes, I do. I feel everything you feel.”

“I want you out. Get out now.”

“Never.”

I tore open the cabinet under the sink, yanked out a bottle of Formula 409, unscrewed the cap, and tilted my head back. I didn’t care if it killed us both.

Around two in the afternoon I woke up on the couch. I’d spent the morning puking 409.

“Aw, morning sickness,” Bruce had said, as he headed out the door. “Don’t worry about me, I’ll get the bus.”

I tried to sit up. The room was still spinning from the household cleaner, but I was alive. I felt myself for Chris but there was nothing. Nothing. I put my face in the couch and cried. “Chris, Chris, come back. Please. I’m sorry. Give me another chance.” Then I felt the stirring in my pelvis that had become so familiar and comfortable these past few months. I wrapped my arms around my waist. “Chris? Chris, are you all right?”

“Huh?” He was groggy but alive. “Yeah, the cleaner mixed with your stomach acid worked as a pretty strong hallucinogenic. I saw a jade Buddha sitting on your colon. I guess you’re pretty disgusted with me at this point.”

“No. I’m happy to feel you. I’m sorry if I hurt you.”

“Let’s go to sleep.” He rubbed the back of my belly, which made me drop off quickly.

I woke up again at six and knew by the lightness I felt that Chris was out of me. I stood up and felt like I could float. I unzipped the bloody slipcovers off the couch and went upstairs to wash up and change. Everything was quiet and peaceful, and I walked through my house alone. Outside, Chris emptied the grass cage of his mower into a lawn and leaf bag. Later, I heard his mower over at the Leonards’ house join the chorus of other mowers in the neighborhood, but I can always pick out Chris’s. It’s the one that’s low, sweet, and unwavering, like a lover’s voice.

Babyproofing

My wife dreams the pantry shelves buckle and the baby is buried under a thousand cans of beans. She dreams Caroline gets sucked into the chimney; we can hear her gurgle and sing softly to herself—“Rock of Ages,” to be exact—but we can’t get to her. We don’t even know what chimney to look up because, in the dream, the house has twenty, thirty chimneys and more keep popping up—bing! bing! bing!—through the roof. She dreams the baby falls out the second-floor window. She could catch her if she could get outside in time, but something grabs at her ankles. An enormous lobster claw pulls her down into the floor, below the foundation, and by now she’s jerked herself awake. It’s me that’s holding her ankles, holding her down. I’m the claw, right?

“No, Walter, not every bad dream is about you.” She moves away from me, swinging her legs over the side of the bed and stepping around the porta crib, where the baby still sleeps after all these months despite my insistence she sleep in her own room. “Look deeper,” she calls in a whisper, over the tinny alto of her urine hitting water.

I don’t think about dreams. Once a year, when the annual report is due, I dream that my father is a Greek shipping magnate, sailing on the open sea in his magnificent vessel, and I’m bobbing around in a dinghy tied to the back.

Sarah returns to bed but can’t get back to sleep; she’s worrying about the Casablanca fans coming loose from the ceiling. I’ve checked them, I tell her. I’ve hung from the poles. I’ve done chin-ups on those fans. She tries warm milk. She pees again. We lie awake thinking about ceiling fans falling down and what they could do to a nine-month-old.

Mitzy Baker, president and CEO of Baby Safe, Inc., stands in the center of our living room, taking everything in like an admiral on the deck of his flagship. Right away I remember the fireplace equipment that hangs over the marble like huge dental tools, the drop-leaf maple table my great-grandfather smuggled out of Russia, the Sunufu fertility statue teetering on the low oak stand.

“I know about the fireplace equipment and the table,” I blurt out.

Mitzy Baker manages a phony grin that mirrors the smiling kittens embroidered on her cashmere sweater set. Her starched hair is pulled into a matching kitten band that seems to be pulling everything up; her face, her mouth, her neck, even her shoulders are too close to her ears.

Now and then she gives an obligatory smile to the baby. But Caroline’s not falling for it. She wrinkles her eyebrows and drools. That’s my girl.

“Incidentals,” Mitzy Baker says. “Those are the easy things. The table, the fireplace equipment, the art, these sharp edges.” She points to our glass coffee table with the point of a navy patent-leather pump and writes something down on a clipboard. Any minute the Gestapo will bust through the door and whisk Sarah and me off to the basement of a building where we’ll be judged by a panel of babies in fiberglass bike helmets. What do I feel so guilty about? I called them, didn’t I?

We go into the library. I know the bookshelves are wrong. I don’t need Mitzy Baker to tell me the baby could pull them down on top of herself. Yes, I could have spent twenty-five cents on an elbow joint and attached the shelves to the wall before

this chilly, judgmental woman came into our home. But I’ve been busy with work and Sarah with the baby and that’s what I’m considering hiring Baby Safe to do, right? She shakes the shelves to see just how unsteady they are, how reckless we are, how we care more about the beauty of our house than the safety of our child, and writes something else down on that blasted clipboard.

“Incidentally,” Mitzy Baker says, “a head could get stuck in here.” With her blue pump, she points to a space in the wrought-iron banister we had made in Virginia.

“I’m not pulling out the banister,” I whisper to Sarah. “We spent two thousand dollars on that banister.”

“What do you suggest?” Sarah asks. “Should we replace it?”

“No,” I say. “The baby’s just going to have to learn not to stick her head in there.”

Mitzy Baker stares at me for a moment. Something’s clipped the wire that keeps my posture straight. I feel myself slouch two inches. “Again,” she says. “The banister is an incidental. We fix it.”

She manages a nice subservient smile. I rise back up to my full six feet two.

“Have you thought of covering the floors?” Mitzy Baker asks, tapping her shoe on the hardwood in the living room. “My pediatric neurologist friend says head injuries are what put his kids through college.”

Sarah squirms. The thought of head injuries, along with faceless baby snatchers in black vans with no license plates, keeps her up at night.

“Covering the floors with what?” I ask.

“We have a three-inch rubber padding. It’s firm but has give. It comes in taupe, wheat, cobalt, and toffee. It’s a wonderful product and not unattractive.”

Sounds beautiful.

“May I?” she asks, gesturing toward one of our Moser dining chairs.

“Please,” Sarah says.

Mitzy Baker sits at our Moser table, takes a calculator from an accordion envelope, and gets to work on the clipboard. She pivots her sharp heel back and forth on our newly refinished wood floor while she pecks out numbers. The calculator adds and advances, making sounds like a sick man clearing his throat. I wait for her to move her foot aside to see if she’s left a mark. She pauses for a moment to look around the dining room.

“Lovely table.” She taps on the cherry wood with a white frosted fingernail. “Is it Swedish?”

“It’s from Maine,” I say. It’s a Moser, for Chrissake.

Ten minutes later, after Sarah and I have been throwing glances at each other, arguing with our eyebrows, shrugging and clasping our hands and offering coffee that keeps getting refused, Mitzy Baker puts her pen down, laces her fingers together to make a shelf for her starched head, and rests her chin on her hands.

“What do you worry about, Mrs. Peel, at night, lying in bed?” Her voice is gentle. “What’s your fantasy? What’s the worst thing that can happen?”

A tear splashes on the Moser table. I move over to my wife, but it’s Mitzy Baker’s hand that Sarah takes.

“Shhhh. Putting words to the feeling will make it better.”

“I can’t stop thinking about—”

“Let’s stop this,” I say.

“No.” Sarah slides my hand off her shoulder. She straightens in her chair. “There were those girls who disappeared. Their mother went inside to get sweaters—” Sarah breaks down.

“The Whiley sisters,” I say. “That was twenty years ago.”

“Those things happen, yes.” Mitzy Baker’s hand smooths my wife’s hair. “But rarely, so rarely. Your house, Mrs. Peel, is your daughter’s worst enemy.” Sarah picks up her head. “We are dealing with a weapon here, Mrs. Peel. A dangerous weapon.”

I look over at Caroline, sitting on the entrance hall floor, gumming the blue rings of her Wiggle Worm. “What’s the bottom line?” I ask, rubbing my thumb and index finger together.

The women look at me like I’m Goebbels. Then Mitzy Baker looks down at the clipboard, as if she doesn’t have the price tag recorded on her synapses.

“Give us complete access and control of your house, Mr. and Mrs. Peel. For three days your house is my house. We’ll create a safe haven for your little one.”

I look over her shoulder at the grand total. “Four thousand dollars?”

“It’s a very good deal if you break it down into hours and manpower. We leave no stone unturned—and believe me, neither will your daughter if you don’t do some serious babyproofing.” She looks up toward the attic as though the place has a terrible secret. Then she looks sadly over at Caroline, who’s pulled herself up on the glass coffee table. We’ve been so busy thinking about how to keep her alive, we missed the first time she ever stood up by herself.

“All I wanted was a couple of cabinets locked and some gates on the stairs,” I say to Sarah, as we watch Mitzy Baker stroll down the front walk of the house.

“These are lovely trees,” Mitzy Baker calls back to us, looking up at the beeches. “They must be ancient.”

“We like them too,” I call back. Two squirrels spiral their way up a trunk and disappear into the deep foliage. A cardinal mom comes in for a landing with dinner. “Preposterous,” I say to Sarah. “Sheer and utter crap.”

“Someone must be buying into this crap,” Sarah says, as we watch Mitzy Baker slide into her leather-smothered Lexus and wriggle her hands into a pair of black driving gloves.

That night I dream of floors giving way to a black hole. I dream of explosions and shellfire from German sorties flying over the house and the amplified voice of the Wehrmacht: “Achtung, Achtung!” I dream of tree limbs falling down on my wife and baby, tree limbs that become quivering human limbs. I dream of giant Sunufu statues crashing down in a crumbling temple, blocking the exit as the ceiling caves in around my family. My father sails down the street in his sloop, wearing a double-breasted blue blazer and white pants. I call out for help but there’s a tornado in my house, and the thunder and swirling wind carry my voice away.

“That’s just going to look atrocious,” I say.

“Walter, we’re not going to have House Beautiful for a while,” Sarah says, as one of Mitzy Baker’s worker bees unscrews the retaining bolts of the wrought-iron banister from the stairs to replace it with a red inflatable hot dog–shaped barricade.

“Caroline’s barely moving yet.”

Mitzy Baker glances at Sarah from the dining room, where she’s cataloging and packing up our crystal and china, as if to say, Husbands, what can you do? She looks different today. I almost didn’t recognize her without her hair band and blue pumps. She wears an old pair of paint-splattered jeans and a man’s chamois-cloth shirt. Her face seems younger and friendlier as she goes to work with her hammer and screwdriver, installing latches, electrical tubing, lid locks on the toilets, outlet covers, elbow joints, gates, and foam rubber padding.

At lunchtime I leave work and drive home so I can check on the Baby Safe people. Not that I don’t trust Sarah’s judgment, it’s just I know she’s busy with the baby and might not be able to keep the necessary watchful eye on the workers.

I turn down Meadowbrook and see that the skateboarders are out in force. Nine twelve-year-old boys have skipped school and taken over the street for its smooth pavement, low curbs, and cars to challenge. I expect problems. But as I approach, a skinny kid with his hair cut high above his floppy ears, and floppy pants and big shoes to balance, has found a swell in the sidewalk that is perfect for lifting yourself up in the air, pulling your knees to your chest, falling off your board, and landing on your elbows. The street clears so I can pass scot-free.

I pull up in front of our house just as a couple of muscle guys in sweaty T-shirts are bringing out the ceiling fans, lugging them across the lawn and passing them up to a crew-cut sweaty guy in the back of a moving van. An old man in railroad-conductor overalls comes from around the back of the house carrying the Sunufu fertility statue, looking closely at its immense breasts and behind, wondering why it’s considered art.

“Careful with that,” I say. “

That was used in actual ceremony.” He looks at me as though I’ve spoken Swahili.

There’s a blizzard of activity in the house. It takes me a minute to get my bearings. The first thing I notice is a college-age kid under the dining room table unscrewing the legs. “Hey,” I say. “The table’s not going anywhere.” He ducks his head out from under.

“I was told to pack the dining room,” he says.

“No, no, no,” I say, as the Moser chairs are moved out, two by two, by the crew-cut hit squad. “Put those down!” I say, “Put the chairs down; they’re not going anywhere.”

“We were told ten dining chairs to the truck,” a thug with a scar on his head puffs. He produces a sheet of onionskin paper, which is covered with tomato stains from a meatball sub.

“Well, that’s wrong,” I say.

“You’ll have to talk to Mitzy Baker about that,” he says, going out the front door with the chairs, banging the legs on the doorframe.

I head upstairs, looking for Mitzy Baker, moving against the wall so a couple of men in blue coveralls can get by with my 27-inch TV, which Mitzy Baker said was wobbling on its stand. “Where’s Mitzy Baker?” I ask.

“Haven’t seen her, sir.”

“How about my wife?”

“No, sir.”

There’s another college-age kid in my office yanking the nails out of my bookshelves, and through an open door I see a young woman in a gray hooded sweatshirt packing things from my darkroom. No one goes in my darkroom.

“Nope, not in here,” I say, barreling across the room. “We’re not touching any of this.” I snatch a stack of stiff underdeveloped eight-by-tens I took of Sarah and Caroline in the woods near our house.

The woman looks up at me with her mouth open. The young man starts to drag out a box of developing solutions. I grab hold of the other side.

“Hey, I just said this room doesn’t get touched!”

“Talk to Mitzy Baker,” he says, not even looking at me, yanking the box out of my grasp.

I rush downstairs. “Where’s Mitzy Baker?” I ask four more sweaty crew-cut men who are carrying Sarah’s great-grandmother’s harpsichord down the front steps of the house.

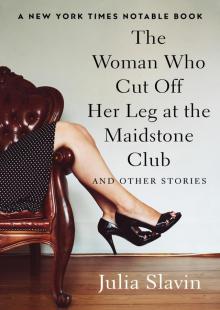

The Woman Who Cut Off Her Leg at the Maidstone Club

The Woman Who Cut Off Her Leg at the Maidstone Club